Advanced Fellasophy 03

On Popper’s “Paradox of Tolerance”

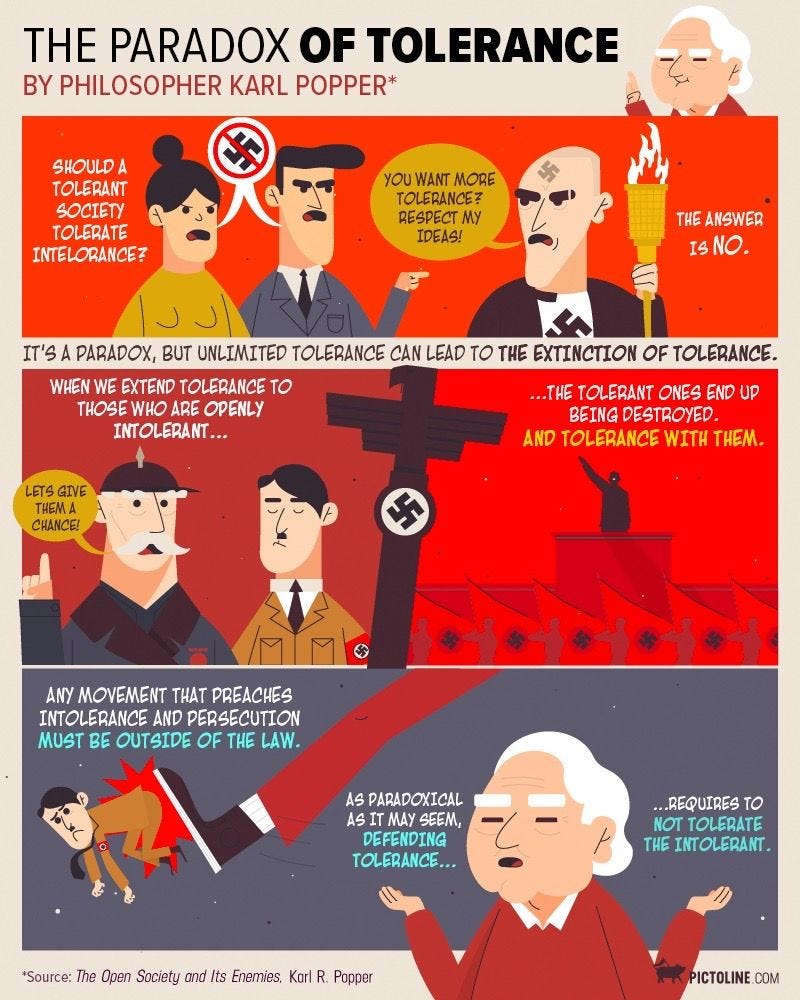

If you spend enough time around X/Twitter, you’ll probably stumble upon the following meme:

As far as memes go, it’s pretty straightforward. However, it’s also very misleading. This is a distortion of Popper’s view, and a misrepresentation of the Paradox of Tolerance.

Once properly understood, Popper’s discussion of the Paradox of Tolerance is actually far more interesting than what’s presented in the meme. It’s a lot less pithy, too, but what can you do?

Part One: Examining the Text

One thing to note is that the Paradox of Tolerance—hereafter “PoT”—is not Popper’s view. Indeed, the only reference to the PoT in his seminal The Open Society and Its Enemies comes in a footnote, which I will reprint in its entirety:

Less well known [than Plato’s other paradoxes] is the paradox of tolerance: Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.—In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.1

There are a few important notes and takeaways here.

First, the PoT comes up in the context of a discussion of Plato’s arguments against democracy; in fact, Popper attributes the basic formulation to Plato himself! Popper says that Plato uses the PoT as a reason for why we should reject democracy and embrace his form of enlightened dictatorship (the Philosopher-Kings model).2

The original formulation of the PoT is a criticism of democracy. In Plato’s Republic, Plato argues that in a democracy, freedom is “the glory of the State”; that is, it judges itself based on how much freedom the society has, without regard to how those freedoms are used (either for good or for ill).3 No one has any clear idea about what their responsibilities are, so everyone is left to their own devices. It’s like a ship where the deckhands have overthrown the navigator and the captain, and now wonder who is going to get them to shore safely. This is why Plato thinks that democracy inevitably leads to tyranny: as the citizenry abandon their responsibilities and society fractures, they look to the strongman to put society back together again.4

And so, the PoT is part of that line of argumentation. Democracy values freedom, but it passes no judgement about what freedoms are good or bad. As such, people who would overthrow democracy are allowed to pursue that goal. To avoid the intolerance that would come with anti-democratic forces, the democrat must show intolerance to the intolerant. This, says Plato, is a paradox. It is a problem to be solved.

What Popper provides is a means to solve the paradox. So let’s move on to that.

Part Two: Popper’s Solution

Popper’s solution to the paradox is found in two places: the part of the passage above following the emdash (—); and, in a passage found at the end of the same footnote in which we find the PoT. Popper writes:

All these paradoxes can easily be avoided if we frame our political demands in the way suggested in section ii of this chapter [of The Open Society and Its Enemies], or perhaps in some manner such as this. We demand a government that rules according to the principles of equalitarianism and protectionalism; that tolerates all who are prepared to reciprocate, i.e. who are tolerant; that is controlled by, and accountable to, the public.5

Between these two passages, Popper’s solution to the PoT is as follows:

We must not suppress any philosophy, no matter how intolerant it is, as long as its adherents are rational; that is, they are willing to change their mind on the basis of reasons.

We claim the right to suppress any philosophy, “if necessary even by force,” if they abandon the rational enterprise; that is, they explicitly “forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols.”6

The rules for what constitutes a level of intolerance sufficient to warrant suppression are codified in law, administered and enforced by a regime that is impartial and answerable to the public.

Put most basically, the Open Society must allow for some intolerance, as long as that intolerance is playing by the basic rules of discourse. They can spout their baloney, and as long as they stay within the rules, the society can’t suppress them. But if those people start rejecting the primacy of evidence, reject the rules of reason, reject the basic requirements of living peaceably with each other, then the society has a right to defend itself.

This defeats the paradox because of the legal framework in which Popper places this task. Laws are public. In an equalitarian society, they are impartial and administered evenly. People are able to understand them and will know what happens should they step out of line. This is why the following passage is so important:

We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.7

It is not individual intolerant people who are suppressed for being intolerant. Your intolerant uncle isn’t going to be carted away when he vomits his bigoted views next Thanksgiving. Rather, it’s the leaders of movements preaching intolerance who need to be punished. Again, it’s considering “incitement to intolerance and persecution” illegal—not intolerance itself—just as it’s “incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade” that’s illegal.8

What happens to individual intolerant people? Well, they are outside of the Open Society. It is up to us to “counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion.”9 They aren’t suppressed unless they start to spread their filth, advocate for others to abandon reason, or they get violent. Then they can be suppressed.

Let’s summarize by referring back to the meme.

Part Three: Judging the Meme

The first panel asks, “Should a tolerant society tolerate intolerance? The answer is no.”

This is false. The tolerant society must tolerate intolerance, as long as the people who are being intolerant are: a) sensitive to reasons and b) not spreading their views.

But does that mean that the two anti-Nazis must respect the Nazi’s view? No. Of course they don’t have to respect it. They can mock it, they can refute it, they can bonk it, they can refuse to associate with people who hold such a view. This is what Popper means by “keep[ing] them in check by public opinion.”10 Further, they are no less tolerant for doing so. The Nazi is not willing to reciprocate the same level of tolerance as they are, so the Nazi is not afforded the same social standing as tolerant folk.

The second panel says, “It’s a paradox, but unlimited tolerance can lead to the extinction of tolerance. When we extend tolerance to those who are openly intolerant, the tolerant ones end up being destroyed. And tolerance with them.”

This is mostly false. The “It’s a paradox” part is right—that’s Plato’s basic formulation. But the rest of it is right out of left field. Again, according to Popper, we must extend tolerance to those who are openly intolerant. For posterity, here’s the line: “I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies.”11 I mean, that’s pretty clear. Why is it that the tolerant ones are the ones who end up being destroyed? That seems more to be the author’s bias than anything out of Popper.

The final panel says, “Any movement that preaches intolerance and persecution must be outside the law. As paradoxical as it may seem, defending tolerance requires to not tolerate the intolerant.”

This is maybe true? The first sentence is correct. Any movement that preaches intolerance can’t be tolerated. And it’s through the use of law that this happens. And I suppose if we’re really generous with the word “seem,” the rest is true too. But the author seems intent on keeping the paradox intact, whereas Popper’s goal is to resolve the paradox by showing how it’s not paradoxical. Also, the author splits an infinitive, which Popper never does.

But the paradox is only resolved when we distinguish between individual cases of intolerance and movements that incite intolerance by pushing followers to abandon the use of reason. The meme doesn’t distinguish between those two things, and that’s dangerous. We don’t have to respect, or to like, or to even listen to the Nazi, but society can’t suppress the Nazi unless he starts trying to recruit others, or supports violence. Until that time, we have to tolerate the intolerant.

To really see how this works, we need to understand more about the concept of tolerance. So, let’s move to that now.

Part Four: Understanding Tolerance

Toleration is considered a cornerstone of a modern liberal democracy. As such, people most often assume that tolerance was a product of the Enlightenment, co-evolving with concepts like legal rights and freedoms. But the concept of toleration is actually quite old. There’s some vague gestures towards it in Stoic thought, but it really is a product of second-century Christian thought, specifically the works of Tertullian and Cyprianus.

The word ‘toleration’ itself comes from the Latin word ‘tolerare’, which means ‘to put up with,’ or, more accurately, ‘to suffer’. That is, when you tolerate something, you think it’s wrong, but you’re putting up with it—you’re suffering it to continue.

The earliest forms were all considered within the framework of Christianity and were concerned with how Christians should interact with people of other faiths. They recognized that they were, on one hand, duty-bound to tolerate other faiths, but, on the other hand, duty-bound to spread their religion. There was a lot of back and forth about what kind of faiths could be allowed and which couldn’t, the pendulum swung back and forth multiple times—it’s really a fascinating history.

Either way, from that history we see that any conception of toleration has three components:

First, we need to divide all beliefs or practices in to three groups: one, things we agree with; two, things that we don’t agree with but can put up with; and three, things that we don’t agree with and can’t put up with.

Second, we need reasons for why we can allow beliefs or practices we believe to be wrong to continue; that is, what makes a belief or practice wrong, but tolerable?

Third, we need reasons for why a belief or practice gets sorted into the third category; that is, what makes a belief intolerable?

There have been several answers given to these questions. More historical answers focus on permission or coexistence. That is, you let someone do something or are just trying to keep the peace. More modern answers have become stronger, requiring either respect or esteem; that is, you take the ‘suffering’ out of toleration. In more modern senses, toleration requires that you hold each other as moral and political equals.

So, back to the PoT. The first thing we need to do is consider what we mean when we say that we have to tolerate intolerance. More modern conceptions of toleration seem less equipped to deal with intolerance than historical ones. Why should we hold a Nazi as a moral and political equal? We shouldn’t. Their views are too horrid for that kind of toleration. Naturally, social-political philosophers have answers to this, but that’s beyond the scope of this post.

Further, Popper would have been working with a historical understanding of toleration. He supplies answers to all the questions. We allow the intolerant views to exist just as long as they’re private and do not lead to violence. We suffer by having them there, but we recognize that we can’t just stamp them out, due to other prevailing beliefs that we hold; for example, that people have freedom of conscience. These views become intolerable when they are public, renounce the use of reason, and/or get violent. Popper’s account of toleration is thus pretty straightforward.

The takeaway message of this is as follows:

We need to recognize that when we say that we have to tolerate the intolerant, we’re not saying anything more than that we can’t stamp them out. We’re not saying anything about condoning them, or accepting them, or giving them space in the public debate—none of that. It means—only—that we do not use the apparatus of the state to suppress them.

This is a far clearer and far more robust view of how to deal with intolerance than the meme suggests. And it all comes from one footnote!

Closing

If you enjoyed this, or you found this helpful, or even just want to express gratitude, then I would humbly request that you make a donation of any amount to the pro-Ukrainian charity or fundraiser of choice. Bonking vatniks is a form of currency.

Slava Ukraini!

Snarkus Aurelius, PhD

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Plato. The Republic. Found on The Internet Classics Archive. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.html.

Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

NOTES

Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, 581ftn4.

Popper, 581ftn4.

Plato, The Republic, Book VIII.

Plato, ibid.

Popper, 581-2ftn4. Emphasis added.

Popper, ibid.

Popper, ibid.

Popper, ibid.

Popper, ibid.

Popper, ibid.

Popper, ibid.